Philosophical Hermeneutics: General Theory of Understanding

As Edmund Husserl was first to point out clearly, meaning is essentially the discovery of value or importance in something. The value or purpose that an interpreter attaches to a text or to any sort of phenomenon whatever can differ from that attached to it by others (such as the author).

In the case of a text, a new, individual interpretation need not necessarily be a merely subjective or arbitrary one dependent only on the interpreter's favorite theories and the circumstances surrounding his interpretation of it (including the practical purposes involved). The past (such as is represented by an objective text) and the present (represented by a modern interpretation of it) can be fused together through the process of understanding (Verstehen). Understanding is the human faculty of unifying a diversity of circumstances – past and present - objectively given or individually 'subjectively interpreted - into a whole -yet differentiated - continuum.

As Hans-Georg Gadamer puts it: "Understanding is not to be thought of so much as an action of one's subjectivity as a placing of oneself within a tradition in which past and present are constantly fused" (Truth and Method. 1975. p. 258)

The original meaning of a text or any recorded, act can thus be intuited by a well-informed understanding and careful research into the relevant circumstances and then re-expressed within a quite different framework of ideas and language, such as one that is contemporaneous and understandable in the present day and society to which it is to be made available. This can involve departing from the original text's literal content so as to preserve its original meaning (as far as this can be intuited) in an altered form.

That this is possible in principle is implied by the theory of interpretation set forth in the first part of this book. An expression can be separated from the assertion it expresses... through a process of interpretation, which is a re-expression in a derived expression. This can be carried out in respect of entire texts as well as with single sentences.

The method of understanding as the interpretation of actives and purposes which constitute the meaning of all human action as such differs from that of 'extensional' explanation, such as is exemplified in scientific explanation by reference to cause or function. Similarity, the methods intrinsic to the understanding of intentional meaning and the understanding of scientific grounds differ. Hermeneutics relies upon phenomenological method, as its general basis, while the sciences rely primarily on the hypothetical-deductive (or indirect inductive) method.

As a means of introduction to Husserl's phenomenology, the conception of consciousness and its 'intentionality' should first be elucidated:-

The Intentionality of Consciousness: Brentano's thesis

Franz Brentano (1857-1907) first formulated, the thesis of the intentionality of consciousness, which became of central importance, not only to major Continental thinkers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Pointy, but also to modern logicians and some Anglo-Saxon thinkers in the tradition of empiricism.

Some of the main problems with which 20'th century philosophy concerns itself are:-

1) whether consciousness is physically- and causally-determined or whether it is the seat of volition (undetermined conscious will).

2) in what consciousness of will consists and how it is developed - including questions of the relation between conscious, subconscious and 'unconscious factors in behaviour.

3) whether or not consciousness is an entirely subjective experience accessible only to the conscious subject or whether its subjective qualities can be shared - communicated to others with exactness.

Descartes anticipated the modern philosophical concern with consciousness by showing that the most indubitable datum of all is the cogito (i.e. ‘l think therefore I am’). By 'think' Descartes does not refer only to the act of thought, but equally to other acts of consciousness such as doubting, perceiving, imagining and willing. In short, a more appropriate expression of this insight would be 'In that I am conscious, I exist'.

From Descartes onwards the datum of consciousness became an increasingly central concern of philosophy, especially on the European continent. Brentano's ground-breaking thesis of the intentionality of consciousness states:-

Consciousness is always consciousness of an object. By 'consciousness' one may here understand that condition of our minds that makes us aware, whatever it is we may be aware of. If this definition seems circular, that is because the term consciousness can only be understood by reference to the given fact of one's own awareness. It is a primary datum that can only be defined in reference to itself: consciousness itself implies that one is aware of being conscious, so this is an 'irreducible' or non-analysable intuition.

For Brentano consciousness is not one psychic state among other psychic states, nor is it an idea or a re-presentation of anything. He regards it simply to be a 'direction'. So it is not a measurable quantity or a phenomenon like other things or phenomena. Instead, it is an aware directing of the mind towards phenomena. The term 'phenomena' thus refers to 'the entire class of 'objects' towards which consciousness can direct attention (whether these 'objects' be physical things, ideas or other representations of the mind. Consciousness, then, is that which displays or 'discloses' to us whatever it is towards which our attention is directed.

The term 'intentional' has two quite distinct senses. It has been used here earlier in reference to meaning) by distinguishing intentional from extensional meaning. However, when used of consciousness it refers to the capacity of consciousness to direct attention towards an 'object'. In other words, intentionality is a property or quality of consciousness. In this sense it does not imply that consciousness is always purposive or always 'intentional' in its ‘choosing’ or perception of an object. We do not always direct our attention of free choice, so consciousness is not always 'intended' in the purposive sense. Though we speak of 'an act' of consciousness, this does not imply that we are not also involuntarily conscious, such as when our attention is directed towards something without our awarely deciding this. We do not always choose where or to what to give our attention.

As consciousness is always consciousness of an object, there can be no consciousness of nothing at all. When we say 'there is nothing there' we refer to the absence of something anticipated, but lacking. So consciousness still has an object: the background against which the expected object is absent.

Brentano's thesis as the basis of phenomenology

The thesis of intentionality functions in much the same way in Husserl's phenomenology as does the cogito in Cartesian philosophy (i.e. the introspective intuition 'I think, therefore I am'). The intentional act of directing attention - of 'intending' an object - is a form of apperception. The 'object' that is intended is not so much a thing in the external world, but simply an object in the sphere of consciousness. It may be more at the 'objective' pole - as impinging on consciousness from without - or it may arise more at the 'subjective' pole - as being creatively posited by the mind. This is Husserl's starting point in phenomenology, as the following section will discuss further.

In Being and Nothingness (1943 - translated from L’Être et le Néant): Jean-Paul Sartre has argued that consciousness always 'acts', i.e. chooses what to intend, and that this is not unintentional. For Sartre our consciousness is always free to choose. Sartre uses the term 'intentional' in the dual sense of 'directing awareness towards an object' and 'doing so with intent'. Against this, Maurice Merleau-Ponty has argued (Phenomenology of Perception U.K. 1962 translated from the French) that much of our perception is not the result of a free and aware directing of our attention. This applies where we perceive habitually, where our perceptions are pre-structured through social and mental learning.

Edmund Husserl’s Phenomenological Method

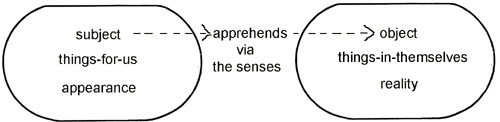

Husserl, the originator of phenomenology, took P. Brentano's thesis of the intentionality of consciousness as his starting point. Since 'consciousness always has an object' and since that object can be either psychical (mental) or physical (material), all such objects together can be classed as phenomena. The term ' phenomena' is taken to mean ‘that which appears to us' or 'that which is given to consciousness' (der. Gr. phainaisthai, to show). Regarding Kant's position - that there are things-in-themselves which can never be known as such but only as they are things-for-us (i.e. appearances) - Husserl aimed to show that scientific certainty about anything can be attained solely by studying things-for-us ('phenomena'), without assuming any reality 'behind' or beyond them (as Kant's things-in-themselves).

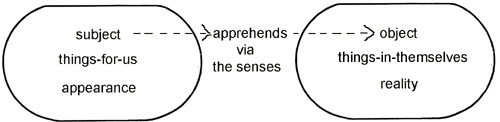

Thus, Husserl held that appearances are reality. The things themselves are exhibited as phenomena, so the assumption that there are things-in-themselves is superfluous. By thus equating appearance with reality, he aimed to develop a method of studying any phenomena, a method which he hoped would provide the basis of scientific certainty in all fields of study, not only in the natural sciences. This ' phenomenological method' was partly inspired by Descartes' method - having the same goal of certain knowledge and in being introspective (i.e. self-reflectively intuitive rather than extrospectively sense empirical). However, its contents and various steps differ considerably from Descartes' stated rules of method.

Husserl's phenomenology was a philosophical theory, of which phenomenological method was but a part. Insofar as the method can be separated from the philosophical position of Husserl, it may be said to consist in a number of general guidelines for observing whatever is presented to consciousness.

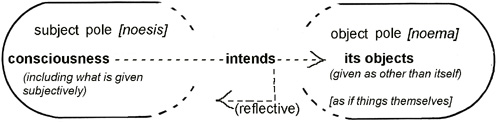

In perception of something in the physical world, for example, there is both an object or objects perceived and a subject who perceives them. The traditional bias of natural scientific empiricism is towards the objects perceived to the systematic exclusion of the perceiver as a conscious, active mind. Natural science strives to eliminate subjective bias, which it regards as simple mis-observation and nothing more than the mistaken sense observation. Its goal is an objective account of common observables from which the individual and subjective moment is eliminated as early in the process as possible so as to leave only generalised accounts that apply independently of the particular observer. Husserl regarded this attitude as objectivism, the one-sided view that the world is a physical reality only in which the subject or the conscious, purposeful mind of a person plays only a superfluous part. Husserl's method would counteract this shortcoming by causing the perceiver to describe, not only the ' objectively-given' object, but also to reflect upon the subjectively-given conditions of the act of perception. This sort of double-ended reflection is termed 'phenomenological reduction' (or also epoche, viewing the perceptive act itself as a composite whole by reflectively putting it 'in mental parentheses' or 'brackets'). Consciousness thus becomes reflectively aware of itself through the perception of its object as appearing to that individual consciousness. This first step, of ‘bracketing' or ' phenomenological reduction' of the act of perception requires) in Husserl's view, that one suspends any judgement about the actual nature or type of existence the phenomenon observed may have in order simply to view and describe it as it appears.

An Example of Phenomenological Method

Suppose one is attempting a scientific observation of the behaviour or animals which requires that we study the nest-building habits of some species of bird. In observing the behaviour of the bird concerned and so in describing this 'object', one may unquestioningly note what one sees and hears as the given facts, omitting to note the manner in which one saw or heard or how one interpreted the various movements and calls. This is to omit the facts-as—perceived or as 'taken in' by the observing mind with its selective and formative influences. One concentrated on the givens (data) to the neglect of the selected viewpoint or the 'taken' aspect (capta). In ornithological fieldwork, of course, the observer's position and behaviour may have an influence on the situation and affect the behaviour of the bird observed, whether directly or indirectly. Natural science takes account of such facts only insofar as necessary to establish what constitutes the bird's behaviour independently of the observers’ influence. Yet just as important in evaluating the accuracy of the description are the ideas and attitudes that the observer brings into the observational situation. The scientist's preconceptions about the nature of birds, or of living beings generally will naturally 'colour' the concepts and terms employed in arriving at a description. The observer's own experience of other species of bird or of other similar phenomena, as well as the theories already developed and assimilated by the observer serve to pre-structure the observation itself, as may also a range of practical considerations extending from what the researcher hopes to observe or expects to establish or refute, what scientific or other significance positive results could have, what would constitute a positive result from the viewpoint of current expert opinion or one's own hypotheses and assumptions generally.

Clearly, such considerations can affect both the act of observing and the descriptive results, since such fore-conceptions (or 'pre-judgements') tend strongly to structure the observing consciousness in a particular direction. This raises the question: can one be said to observing objectively, neutrally recording the facts as they are? What one selects as significant will doubtless vary according to any previously adopted standpoints. If one observes from the viewpoint of behavioural science, one is likely never to consider hypotheses that would be natural to those who live close to the same animals in nature, say as hunter or simply as observer of the seasonal relationships of that species of bird with the entire ecology of the area. If one has adopted a purely mechanistic physical theory as the starting point, one will attend to different aspects of the birds' behaviour than if one has adopted the starting point that animals can have means of interpreting through intuitive faculties or even organs of sense other than we are acquainted with ourselves.

Therefore, on the whole the facts are likely to be interpreted - without due reflection if one excludes the subjective variables from systematic consideration. To regard scientific observation as straightforward registration of sense data, recording something given quite 'objectively’ to the observer is what Husserl calls the 'naive, natural attitude’. It is to overlook the pre-conditioning subjective components of experience. When we stay at the natural attitude, we do not reflect upon the interplay between observer and observed, for we remain at the pre-phenomenological viewpoint, which excludes self-reflection.

The natural sciences are based on the natural attitude, from which they have developed a theoretical attitude. Whereas the natural viewpoint is one of being involved with the concerns, activities, goals and values of the world wherein we live, the theoretical viewpoint limits itself to one aspect of that world - its material givenness. The theoretical attitude starts from a common sense view of reality as an object before us to be explained and sets about to perfect means of making such explanations precise and general. Despite the critical faculties developed in natural science to perfect its methods and theories, it assumes and overlooks the world of practical concerns wherein it arises in the first place and from which it derives its eventual meaning as an activity within society and world culture. Such considerations are regarded by pure science as extra-scientific, not forming a part of the theoretical task of science to investigate.

To adopt a third attitude - the phenomenological standpoint – Husserl requires that we include the pre-scientific concerns and their accompanying assumptions about the nature of-the world and human life's goals and nature in a methodical approach. In scientific practice it involves including ourselves in our reflection upon the observational whole. Only in this way, by 'bracketing the natural standpoint’ and its derived theoretical concepts can we reach an essential appreciation of phenomena. By this 'phenomenological reduction' we can in reflection on the act of observation in question become aware of our pre-conceptions and thus separate out our own influence so as better to recognize what is objectively given and what is given (or ‘taken’) subjectively. This strives towards a description of the objects themselves.

Back to the Things Themselves

The above slogan was suggested by Husserl as the overall programme of phenomenology. It implies arriving at a pure, pre-theoretical appreciation of phenomena altogether, free from assimilated theories and psychologically or socially-inherited preconceptions. Only by becoming aware of the mental predispositions we bring into any form of observation situation can we cleanse perception and discern what is actually given to consciousness. The things themselves are obscure to consciousness only insofar as consciousness is clouded with prejudices, for this is not the Kantian concept of things-in-themselves, which are eternally obscure to consciousness. This difference can be represented by simple diagrams.

For Kant there was a definitive and permanent separation between the perceiving, knowing subject and the empirical object (unknowable in itself) as follows:-

|

For Husserl, however, subject and object were but two relatively distinct poles within the sphere of cognition, the one being mutually-related to the other- the sphere of cognition (appearance as reality)

|

At the natural attitude, which 'naively accepts nature as given', one tries to eliminate subjective givens, which include the psychical or mental correlates in the mind of the subject. The natural attitude focuses all attention on its objects as noema, excluding noesis methodically.

By refining the natural attitude in the attempt to reach accurate scientific generalities and empirical demonstrability, the scientific theoretical attitude of 'naturalism' arises and is exclusively objectivistic (i.e focused on noema alone as being real).

The given phenomena, however, always include both a subjective and an objective aspect, both noema and noesis. Only when both are made aware through phenomenological reduction can a complete observation be achieved, Thus, Husserl holds phenomenology to be more empirical than natural scientific sense empiricism because it does not artificially limit the field of its objects to natural objects. It includes subjective data. It makes no pre-judgements as to what entities are in readily - such as whether they have existence as physical entities or are 'mere appearances', it simply describes all that is given to consciousness, noting whether it is given as belonging to the subjective or the objective pole of the sphere of cognition.

Further, no consideration of usefulness of an observation should enter, such as whether the observation accords with a hypothesis or can be employed to justify a standpoint, for at this stage the aim is merely a pure and unbiased description.

In making such a description, one takes account of the nature of the object under study insofar as it appears as independently given, its apparent characteristics, particular qualities and so on. This mode of the observation focuses on the objective pole, on the object-as-intended (noema). A second mode focuses on the intending consciousness (noesis). This mode includes reflectively noticing 'how' or in what manner the object appears. The manner may be distinct or vague; it may show itself in a particular sequence or hierarchy of aspects or else simultaneously. It may awaken emotion or memory in the subject or it may remind of similar instances, contrary instances or make other strong associations. Such facts as these - and there can be an almost limitless range of them - may be relevant to an observation and make up the subjective data (or rather the capta) of the act.

Phenomenological method and self-observation

In carrying out a phenomenological investigation, the researcher will of course already have determined the general area of phenomena considered relevant to the specific purpose of the investigation. Further, the observer must be trained in the method, just as a natural scientist must also be trained to carry out accurate and reproducible empirical observations. Therefore the phenomenologist must select what sort of phenomena are relevant to the chosen purpose of the investigation. This selection must not be made on the basis of theoretical considerations so much as from an open-minded regard for the phenomena themselves to the extent that he is already acquainted with them. The practical and conceptual assumptions made in formulating one's problem approach and de-limiting one's chosen field of phenomena must not be disregarded as they form the initial subjective data of the project. Particularly where the subject under study is psychological or social in nature, it may be most appropriate to begin from self-observation. For example, in studying the role of habit in social acts or the nature and function of will power in attaining social goals, one's own experiences provide the basis of one's understanding of these phenomena and a valuable source of experiential (i.e. pre-scientific empirical) materials for further phenomenological investigation and analysis. Though such experiences are particular and individual, they are not necessarily 'merely subjective'... they are experienced phenomena which may well contain the essence of such experiences at large. Further phenomenological analysis of them - a step Husserl called 'eidetic reduction' can isolate the essences of such experiences and lead to eventual recognition by other investigators and the test of their inter-subjective validity.

The study of essences: Eidetic Phenomenology

For Husserl, 'Essence' is that about an object which distinguishes it from another sort of object and which never appears without its particular object. After the steps of bracketing and phenomenological description of the sphere of cognition, a further step - the eidetic or essential reduction -is made. From the data so far accumulated, one seeks to isolate the essences of the phenomena in question. This step also involves reflection, a process of mental comparisons and substitutions where one varies the diverse aspects of the given phenomena so as to arrive at the constant characteristics or essences. Whatever remains a necessary constituent under any conditions wherein the phenomena appear constitutes the object's essence, its intrinsic element or elements.

Consider an example of study of a particular class of psychical phenomena. The phenomena known as periodic depression and – conversely - of feelings of self-satisfaction may be studied phenomenologically by a psychologist or psychiatrist. A natural starting point would be the investigator's own experiences of these states of mind. An intuitive or introspective analysis of the personal data would involve reflecting on a range of variations of depressions or feelings of self-satisfaction until the constant subjective qualities are arrived at. One may find the constant factor in periodic depression to be connected with a sense of the futility of one's work as a means to improving the quality of one's own and/or other people's quality of life. Similarly, feelings of self-satisfaction may occur only when events make it evident that one's work is proving useful to others in improving the quality of their lives. Whatever the case, the introspective method has as its object given phenomena, not mere subjective Imaginings... provided one has followed the precepts of phenomenological method with care and rigor.

To extend the example above to show some of the further implications of phenomenological method, one may compare a number of different individuals' introspective analyses of their periodic depressions and feelings of self-satisfaction, relating their results mutually and correlating then with parallel studies in different areas. Another parallel study may take as its phenomena the experienced effects of negative reporting of events, such as the catastrophes, wars and human tragedies that dominate the news media. The essence of reported news may prove to be that it constantly projects a world picture of tragedies that we are powerless to prevent or influence as individuals. If so, phenomenology provides the basis for a hypothesis about the degree of connection between increasingly widespread periodic mental depression and news reporting.

This takes the study to a more general level, after the accumulation of separate studies of essences of phenomena in diverse areas. Husserl planned a 'structural phenomenology', which would become feasible by relating various groups of phenomena through a comparative study of the overall structures discernable in discovered essences at the general level. The structure of essences that structural phenomenology would investigate should accord with insight into their phenomenal interrelations in the world of experience at large.

A further aspect of phenomenology is the study of the origin of such phenomena, say, whether they are psychologically internal to the individuals concerned, whether caused by objective factors (such as by physiological changes in the body) or whether motivated by social, factors external to the individual's control. The study of 'genetic essences' would thus also regard the origins of these elements of experience in social-historical conditions or in evolutional terms.

Depending on the nature of the phenomena under consideration and the problem which directs the investigator to them, different types of research technique may be called for. Research techniques are not to be confused with phenomenological method. Techniques are specific procedures designed for testing specific types of assumption. Scientific techniques developed for the study of natural events will seldom be directly applicable to the study of psychological or social events. In some cases observation under natural conditions may be preferable to observation under controlled experimental conditions. Other techniques that support phenomenological method are the analysis and interpretation of texts, interviewing, case analysis, statistical surveys or participant observation. Self-observation is frequently an appropriate starting point at the least, while for Husserl', self-reflection in the technical phenomenological sense is a prerequisite of all scientific research.

Evaluation of Husserl's phenomenological method

Husserl's work has given rise to a wide variety of philosophies, hermeneutical theories and specific researches in most of the human and historical sciences, many of whose originators express allegiance to phenomenological method in one form or another. There is, however, widespread consensus that phenomenology cannot provide the basis of scientific certainty - of rigorous objectivity - certainly not to the full extent to which Husserl aspired. The reasons for this are complex, yet the chief reason probably lies in a central assumption of Husserl... that pre-conceptions can be eliminated so as to allow a clear and unbiased apprehension of things themselves. While phenomenology doubtless contributes much in making its user aware of mental prejudices and distorting pre-judgements, it fails to account for the fact that some form or another of fore-knowledge is always necessary in any sort of understanding. Such fore-knowledge must always be made up of just those variable social and cultural assumptions that Husserl saw as clouding our view of phenomena. Without assumptions of any sort there can be no knowledge, however certain or generally valid it be.

Doubtless partly for this reason, phenomenological studies by researchers belonging to basically differing schools of thought have failed to lead to the establishment of an accepted science of essences. Instead, phenomenology has opened for a whole range of investigations with different starting points and conclusions that are seldom easily comparable to one another. In short, no broad consensus has been achieved concerning what are the essences in the diverse fields of scientific enterprise.

Nonetheless, phenomenology is an established feature of the European intellectual climate and has opened for a broad debate on the foundations of science and the questioning of science as a purely descriptive, theoretical undertaking. Its normative and pragmatic origins, the values and purposes underlying its endeavours, have become a focus of interest and research generally.

Summary Statement of Husserl's Phenomenological Method

Phenomenology describes the world for us as we experience it from the •everyday' natural viewpoint, not as it supposedly could be 'in-itself. Phenomenological description gives an exhaustive account of appearances, attaching no judgements to its observations as to whether the phenomenon is physically real or not. The world which we meet and describe must not be pre-conceived only as a space-time field populated only by matter, it must be observed for what it usually and directly appears to be, equally much a world of values, actions, practical purposes as a world of neutral scientific facts. Anything that consciousness can direct its attention to and 'intend' as 'an object' - whether apprehended by sense perception, by reasons, by imagination or by other forms of intuition - can become part of the subject matter describable by phenomenologists.

The Method, cannot strictly be graded into systematic steps, for the process of phenomenological investigation can often retrace its own steps in all directions, nonetheless, the following phases will occur in phenomenological study:-

1) Bracketing the natural standpoint. Observe phenomena as they appear without regarding any use they would usually serve to you, whether practical or theoretical. Neutralise one's own normal purposes, requirements, expectations, pre-suppositions and theories so as better to allow the phenomena to 'step forth' for what they themselves appear to be. (Back to the things themselves, not the things-in-themselves).

2) Describe what appears to one's consciousness, simply observe and record.

3) Distinguish in description between the two 'poles' of consciousness.

| The subjective pole 'noesis' | The objective pole 'noema' |

| where attention rests more upon the object-as-intended by the consciousness-as-it-intends. Describe in what manner a thing appears, how clearly, to what sense etc. |

where attention rests more upon the object-as-intended by the consciousness-as-it-intends.Describe its position in space-time (if any), what accompanies it, its characteristics, properties etc. |

4) Isolate and describe the essences of phenomena. Isolate that which distnguishes the object‘ from other objects of comparable kind

and without which qualities/circumstances etc. it never appears.

From Phenomenology to General Theory of Understanding

There is an intimate relation between understanding and interest. The general meaning of interest is usually to perceive some purpose, in the "widest sense of the word purpose: a goal, an end possibly worth aiming for. The purpose of any mental 'act of understanding' could be purely practical - to solve a necessary material problem or highly abstract one -to investigate metaphysical concepts out of a desire to know things in general.

The direction in which we choose to develop our understanding is decided by interest. Some such interests are institutionally-determined by a collective body or by a society as a whole. At a school or university some of the directions of interest are decided by group consensus. Those who choose to study there will tend to extend their understanding in ways for which cultural patterns already exist and are embodied in set courses, study programmes, etc.

One's 'horizon of understanding' is defined on various levels and in many ways. To 'widen one's horizons' as the expression goes is to take in new views, adopt and integrate certain other 'horizons' within one's own such as those opened by a particular book or theory etc. One usually encounters new phenomena within the practical process of living and attempts to understand them by relating them to the ongoing projects of one's life altogether.

Heidegger's Existential Theory of Understanding

Martin Heidegger (Being and Time 1928) describes phenomenologically the process of understanding as being an essential constitutive of the human being (Dasein). (Literally: Da = there, sein = (to) be; therefore Dasein is 'being there'). The human is that being which is in-the-world and the characteristic of 'being there' is existentially inseparable from finding oneself as (a) being 'in-the-world'. The world itself constitutes an inseparable part of - the human way of being - the world is that which is continuously revealed to us in our daily understanding of things, in our interactions with objects, other persons and all that life includes. To be human is to have a world, which doesn't mean simply the earth, nor the 'subjective world' of any person, nor the 'common world' or 'public sphere', yet it embraces all of these.

'World' is not the sum of all existing things, nor 'these entities other than man'. It is that wherein the factual human (Dasein) can be said to live. The person's environing world is part of it.

Simply, 'world' is that sphere in which and towards which we act. 'Dasein' means human being. It is a being whose own being is an issue for it. That Dasein can question its own being is part of its constitution. Another such existential is 'Understanding'. Understanding is part and parcel of being human.

The world consists in 'tools' or 'utensils': i.e. all objects that have the possibility of somehow being used by us for our own purposes. We understand things as we come across them and use them to one or another end, or else reject them as unusable. Things (utensils) are not in essence separate from us, for they "are" what we use and thereby integrate in our understanding as it goes ahead towards future ends. Their being is their 'being-for-us'. Only when a thing turns up or 'shows itself in such a way that there is no way we can relate it to any of our on-going projects whatever, does it appear entirely 'other' and as an incomprehensible object 'separate from' us as perceiving subjects. Things appear as utensils, then, in a functional frame of reference. Within this, one thing points to another. The hammer 'points to' the nail, the nail to the plank, the plank to the scaffolding, the scaffolding to the house, the house to a home and so on.

Understanding, as a general way of being-in, can be concretised by referring to cases of explaining, telling, criticising, commentating etc... This 'reveals' Dasein in his whole existence as a futureward project (i.e. as an onward-going goal-seeking being). It shows Dasein's "living-ahead", As a Being-in the-World, Dasein 'understands' what it meets there as 'ready-to-hand' (simply, as having a meaning within the context of the world and its future goals) not merely as 'present—at-hand' (i.e. as detached from any such 'meaningful' context).

Understanding, in Heidegger's basic sense of the word, is both initially and eventually reliant upon placing things in such a functional frame of reference. This we do without abstract reflection, but by the everyday process of pragmatic thought and practically-oriented reason.

In placing any thing, any phenomenon or event, within a functional frame of reference we do not thereby necessarily grasp the entire framework. The home, for example, may imply a family, the proximity of a shop, transport, a school for children etc. Thus the world of others is already implied in - or indicated by extension of - the original frame of reference in our example. Nature itself forms part of this functional whole that makes up our life world (Lebenswelt). Nor is this frame of reference limited to the present; it embraces past experience - both personal and collective - and future plans, again both individual and collective. Understanding is motivated,

at the deepest existential level, by care or concern (Sorge). Sorge shows Dasein as living for the sake of his own existence in that Dasein is always self-concerned or never indifferent towards itself (which includes the principle of self-preservation). It is consequently the basis of the phenomenon of being as a whole, whereby the whole of one's life is collected in each instant and becomes conscious. Understanding, therefore comprehends both the whole 'functional unity' and its parts} the successive events, acts, operations or circumstances which go to make up the inter-related whole. Thus, understanding has a double-nature; it is both comprehension of the whole context and understanding of the part.

It is extended through time, being present in 'the now' in that it directs the practical activity of the moment, yet it is just as much 'in the future', because its nature is to anticipate, plan ahead and relate practical moments towards a future purpose, an end. It is also equally 'in the past' in so far as it preserves the sense or meaning of what has been done or has happened, making use of this in choosing alternatives of action in the present and for the future. It can even 'go back' and retrace events.